Immune Problems in a Four-Day-Old Foal

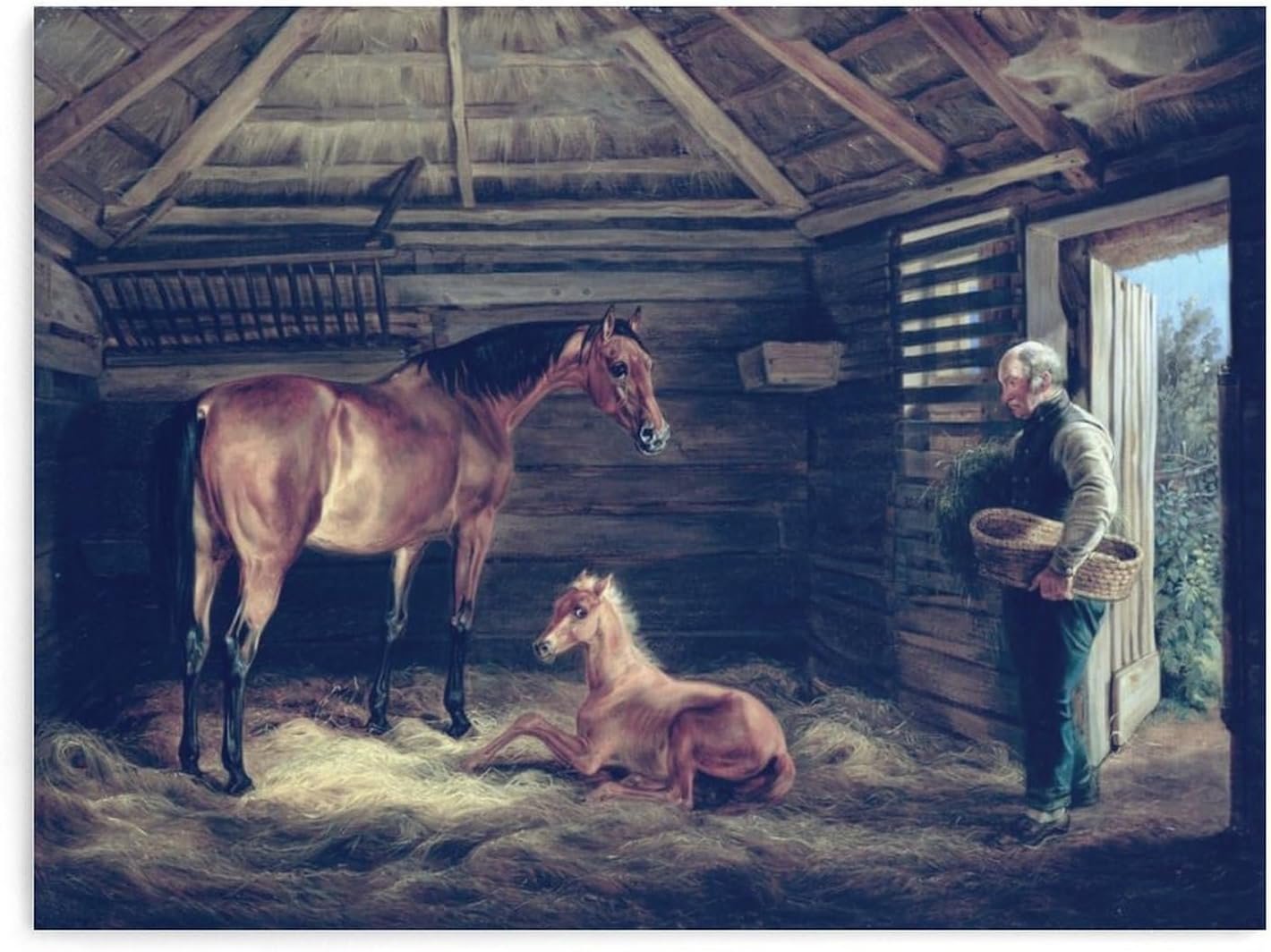

When the owners of Bob, a four-day-old male thoroughbred horse, brought him for veterinary care, they were unsure what was wrong him. He had stopped nursing his mother for the previous 12 hours and just didn't seem to be acting normally. Upon examination, the veterinary staff also noticed that he had blisters in his mouth and between his back legs. He was also bleeding a little bit on his hooves.

Dr. Pamela Wilkins, the head of the Equine Medicine and Surgery Service at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Urbana, was on the case, and her first suspicion was that Bob was having a problem with his immune system.

The nutrition a foal receives in the first few days of its life are key in developing the immune protection the animal will need at the start of its life, but sometimes that immune protection can be too much of a good thing.

Those first few meals, provided by the mother, are called colostrum. It is the first milk that the mother makes for the foal and contains essential ingredients, among them immunoglobulins, which are also known as antibodies. Unfortunately, either too little or too much of this very good thing can result in various diseases for the newborn foal.

In foals a common problem can be what veterinarians call "failure of passive transfer," which means that, for some reason, a sufficient amount of the immunoglobulins did not pass from the mare to the foal. This problem can occur due to a decreased amount of immunoglobulins in the mare's colostrum, or it may arise because the foal either did not nurse and take in enough immunoglobulins or did not absorb enough immunoglobulins, among other reasons.

A second possible hurdle that the foal may have to overcome is if the colostrum contains extra immunoglobulins in error, called alloantibodies, from the mare. Dr. Wilkins says that these alloantibodies can cause some of the foal's red blood cells to be destroyed, resulting in a condition called neonatal isoerythrolysis. This disease results in a decreased ability of the blood to carry oxygen through the body.

Both of these diseases were possible diagnoses for Bob. Luckily for him, a few simple, inexpensive blood tests could be run to determine whether he did indeed have failure of passive transfer. The tests measure how much Immunoglobulin G, or IgG, is present in the foal's blood. If the measurements indicate that the foal doesn't have the normal amount of IgG, then it can be fed extra colostrum or given a transfusion of plasma, the fraction of blood that contains immunoglobulins as well as a few other components that will help the foal protect itself.

Bob's blood test showed that he had more than enough IgG to eliminate the possibility of failure of passive transfer. The next suspected diseases, then, were neonatal isoerythrolysis or a more recently described disease, ulcerative dermatitis with neutropenia (low white blood cells) and thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

Neonatal isoerythrolysis is a disease that can be life-threatening because of the severe anemia that develops and is fairly simple to diagnosis by measuring the hematocrit (or packed cell volume) and performing a blood cross-match with the mother. If severe, a blood transfusion may be needed for treatment. Testing showed that Bob did not have neonatal isoerythrolysis.

Instead, Bob was diagnosed with ulcerative dermatitis, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. Bob had problems with low white blood cells, which made him at risk for increased infection; had problems with clotting his blood because of low platelet count; and had ulcers all over his body wherever friction was present. In Dr. Wilkins' experience, though, simply monitoring the foal and giving supportive care, including antibiotics and tube feeding until his mouth healed, has proven to be just as effective as more involved and expensive treatments. This was the elected treatment plan for Bob, relieving some stress for both the patient and his owners' wallet.

For the next few days, Bob was given intravenous fluids, antibiotics and fed through a tube as his mouth healed. A protective substance called sucralfate was applied to his blisters and also given by mouth to help him heal. These treatments gave his body the time it needed to reproduce white blood cells and platelets and to heal his skin.

Thanks to Dr. Wilkins and the hospital's staff, Bob made a full recovery and was finally equipped with the tools his immune system needed to give him lifelong protection.

For further information on foal health or immunological diseases, contact your local veterinarian.